Mental Health, Person or Environment Metaparadigm?

Would mental health fall under person or environment metaparadigm? This fundamental question drives much of the discussion surrounding mental health care. It’s not a simple either/or proposition; instead, a complex interplay between individual characteristics and environmental factors shapes our mental well-being. We’ll explore how genetics, personality, and coping mechanisms (the “person”) interact with socioeconomic status, social support, and cultural context (the “environment”) to influence mental health outcomes.

This exploration will also delve into the ethical considerations and practical applications of understanding this dynamic relationship.

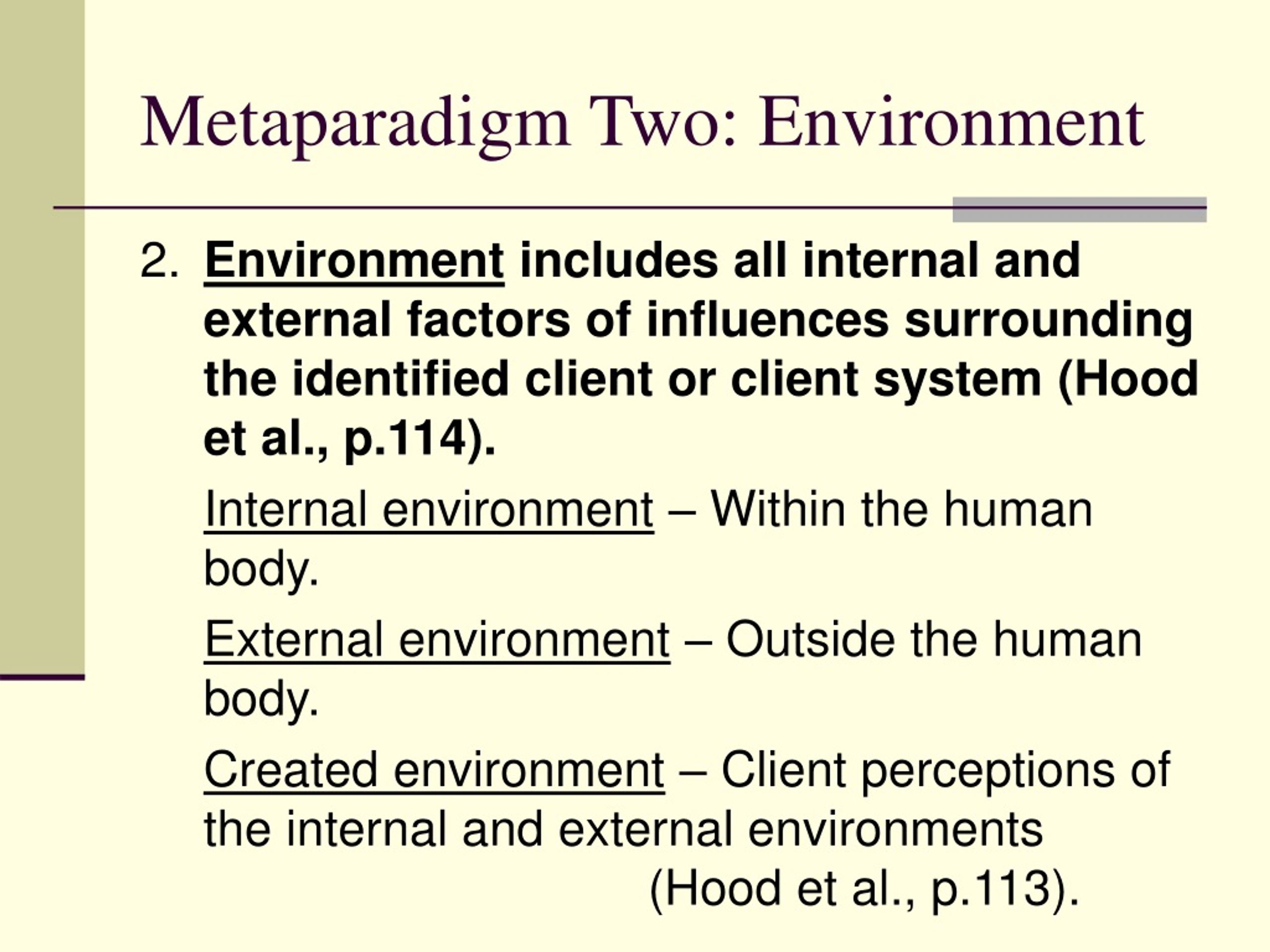

The person metaparadigm emphasizes individual factors like genetics, personality, and coping skills as key determinants of mental health. Conversely, the environment metaparadigm highlights the significant impact of external factors such as socioeconomic status, social support, and cultural influences. However, a holistic understanding requires acknowledging the intricate interaction between these two perspectives. This involves recognizing how environmental stressors can exacerbate pre-existing vulnerabilities, and conversely, how supportive environments can buffer against individual risk factors.

We’ll examine different theoretical models, including the biopsychosocial model, that attempt to integrate these perspectives for a more comprehensive approach to mental health.

The Person and Environment Metaparadigms in Mental Health: Would Mental Health Fall Under Person Or Environment Metaparadigm

Understanding mental health requires a holistic approach, considering both individual characteristics and environmental influences. The person and environment metaparadigms provide a framework for analyzing these intertwined factors. This article explores these metaparadigms, their interaction, and their implications for mental health practice and policy.

The Person Metaparadigm in Mental Health

Within the nursing framework, the person metaparadigm emphasizes the unique biological, psychological, and social attributes of an individual. In mental health, this means recognizing the individual’s genetic predispositions, personality traits, coping mechanisms, and personal history as key determinants of their mental well-being. These factors significantly influence an individual’s vulnerability to mental illness and their capacity for recovery.

Looking after your mental health is super important, especially for young people. If you’re in Yamhill County and want to learn how to help a young person struggling, check out the resources on youth mental health first aid provided by yamhill county public health youth mental health first aid. It’s a great way to make a difference.

On a completely different note, I saw this funny hoodie the other day on Amazon; it said, ” you are bad for my mental health ” – a bit cheeky, but maybe a relatable way to express needing some space!

Individual factors such as genetics play a crucial role. A family history of mental illness, for example, can increase an individual’s risk. Personality traits, like neuroticism or resilience, also contribute to mental health outcomes. Effective coping mechanisms, learned through experience and personal development, can buffer against stress and adversity, while ineffective coping strategies may exacerbate mental health challenges.

Case Study: Applying the Person Metaparadigm

Consider a patient diagnosed with depression. Using the person metaparadigm, we might analyze their genetic predisposition to mood disorders, their personality traits (e.g., pessimism, low self-esteem), and their coping mechanisms (e.g., avoidance, substance use). Understanding these individual factors allows for a tailored treatment plan addressing specific vulnerabilities and strengths. For instance, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) could be employed to address negative thought patterns, and medication could be considered to manage the biological aspects of the depression.

The Environment Metaparadigm in Mental Health

The environment metaparadigm focuses on the external factors impacting mental health. This includes socioeconomic status, social support networks, cultural context, and exposure to stressors such as trauma, abuse, or discrimination. These environmental factors can significantly influence the development, course, and outcome of mental illnesses.

Socioeconomic disadvantage, for example, can create significant stress and limit access to resources, increasing the risk of mental health problems. Strong social support networks, conversely, can provide resilience and promote recovery. Cultural beliefs and practices can shape an individual’s understanding of mental illness and their willingness to seek help. Experiences of trauma and adversity are potent environmental stressors with long-lasting consequences for mental well-being.

Comparing Personal and Environmental Factors

Both personal and environmental factors contribute to mental illness, often interacting in complex ways. While genetic predisposition might increase vulnerability, a supportive environment can mitigate the risk. Conversely, a traumatic environment can overwhelm even the most resilient individual. A balanced approach considers both factors when assessing and treating mental health conditions. For example, a person with a genetic predisposition to anxiety might develop an anxiety disorder if they experience significant environmental stressors, such as bullying or job loss.

Conversely, someone with the same genetic predisposition might remain mentally healthy if they have strong social support and coping mechanisms.

Interaction Between Person and Environment in Mental Health, Would mental health fall under person or environment metaparadigm

The interplay between individual characteristics and environmental influences is dynamic and multifaceted. An individual’s personality and coping mechanisms will shape how they respond to environmental stressors. For example, someone with strong coping skills might navigate a stressful job loss more effectively than someone with poor coping skills. Similarly, environmental interventions, such as therapy or support groups, can strengthen an individual’s resilience and mitigate the impact of personal vulnerabilities.

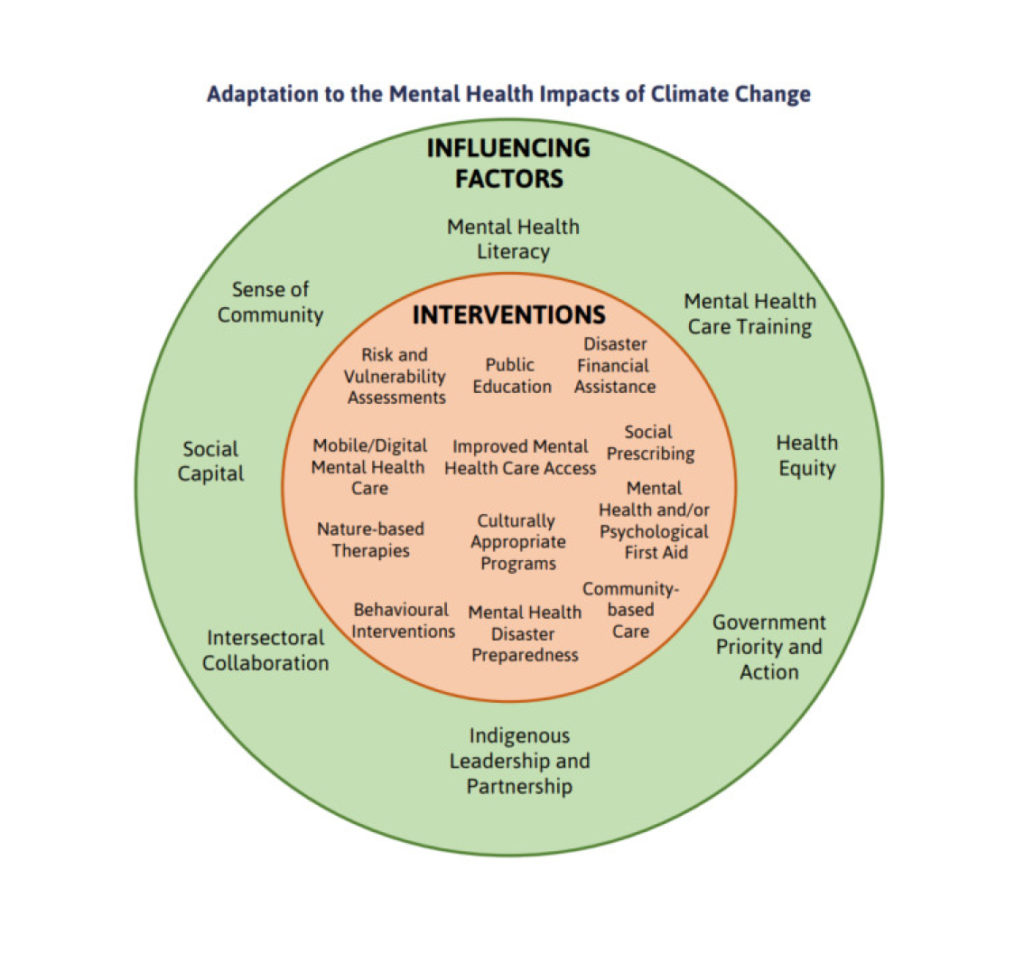

Examples of Environmental Interventions

Environmental interventions aim to create supportive and protective environments. These interventions can include various forms of therapy (CBT, Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT)), support groups providing peer-to-peer support, community-based mental health programs offering access to resources and services, and policy changes aimed at reducing societal inequalities. These interventions address environmental factors and help individuals develop healthier coping mechanisms.

Looking after your mental wellbeing is crucial, especially for young people. If you’re in Yamhill County and want to learn how to help a young person struggling, check out the resources available through the Yamhill County Public Health Youth Mental Health First Aid program. They offer valuable training. On a lighter note, I saw a funny hoodie online – the “You are bad for my mental health” hoodie on Amazon – it’s a quirky way to acknowledge the pressures of life, though obviously not a replacement for real support.

Ethical Considerations of Interventions

Ethical considerations arise when deciding which factors—personal or environmental—to target with interventions. For example, focusing solely on individual therapy might neglect systemic issues contributing to mental health problems. Conversely, focusing solely on societal change might not address the immediate needs of individuals struggling with mental illness. A balanced approach recognizes the importance of both individual and societal interventions while ensuring equitable access to care and avoiding stigmatization.

Applying the Metaparadigms in Mental Health Practice

Mental health professionals use both the person and environment metaparadigms to develop holistic treatment plans. For example, a therapist might assess a patient’s genetic history, personality, and coping mechanisms (person metaparadigm) while also considering their socioeconomic status, social support, and exposure to trauma (environment metaparadigm). This comprehensive assessment informs the choice of interventions, combining individual therapy with social support and advocacy efforts, if needed.

Hypothetical Scenario: Integrated Approach

Imagine a patient experiencing anxiety related to job insecurity. A mental health professional might use CBT to address the patient’s negative thought patterns and develop coping strategies (person metaparadigm). Simultaneously, they might connect the patient with job search resources or support groups to address the environmental stressors (environment metaparadigm). This integrated approach targets both individual vulnerabilities and environmental challenges.

Challenges and Limitations of Applying Metaparadigms

Applying these metaparadigms in real-world settings presents challenges. Limited resources, time constraints, and the complexity of individual cases can make a truly holistic assessment difficult. Furthermore, the interplay between personal and environmental factors is complex and not always easily disentangled. Bias and stigmatization can also influence the application of these metaparadigms.

Alternative Perspectives on Mental Health

While the person and environment metaparadigms are valuable, relying solely on them is insufficient. A biopsychosocial model provides a broader framework, integrating biological, psychological, and social factors. This model acknowledges the interplay of genetics, neurobiology, cognitive processes, emotions, behaviors, social relationships, and cultural context in shaping mental health. Other theoretical frameworks, such as the ecological model or social determinants of health model, further enrich our understanding by emphasizing the interconnectedness of various levels of influence.

Biopsychosocial Model: Integration and Expansion

The biopsychosocial model expands upon the person and environment metaparadigms by explicitly incorporating biological factors, such as genetics and neurochemistry, alongside psychological and social factors. This integrated approach allows for a more comprehensive understanding of mental illness and guides the development of treatments that target multiple levels of influence.

Implications for Mental Health Policy and Practice

Understanding the interplay between personal and environmental factors is crucial for developing effective mental health policies and practices. Policies should address social determinants of health, such as poverty, discrimination, and lack of access to healthcare. Promoting mental well-being requires interventions at both individual and community levels, fostering resilience and creating supportive environments.

Strategies for Promoting Mental Well-being

Strategies for promoting mental well-being include expanding access to mental healthcare services, promoting early intervention and prevention programs, strengthening social support networks, addressing social inequalities, and reducing stigma. These strategies target both individual vulnerabilities and environmental factors, promoting holistic well-being.

Ideal Mental Healthcare Systems

Ideal mental healthcare systems integrate insights from both metaparadigms, offering a range of services addressing both individual needs and environmental influences. These systems provide accessible and equitable care, focusing on prevention, early intervention, and recovery support. They also advocate for social justice and address systemic barriers to mental health.

Ultimately, the question of whether mental health falls under the person or environment metaparadigm is misleading. A truly effective approach to understanding and treating mental health requires considering both. Ignoring either individual vulnerabilities or environmental influences leads to incomplete and potentially ineffective interventions. By integrating insights from both metaparadigms, we can develop more holistic, ethical, and effective treatment plans, mental health policies, and community support systems that promote well-being for all.

Share this content: